Weather: We know it was very cold at the time as Wayne wrote that the local rivers were "strongly frozen over."

Terrain: The terrain between Fort Greenville and Fort Amanda is basically flat, dropping only 57 feet over 44 miles or less than 1 1/2 feet per mile.

Daylight: According to the Naval Observatory, in early January 1794, sunrise was at 8:09 AM and sunset was 5.27 PM, or 9 12/ hours of daylight.

Nighttime sky: The moon on January 2nd was in its first quarter phase meaning half the moons face was visible.

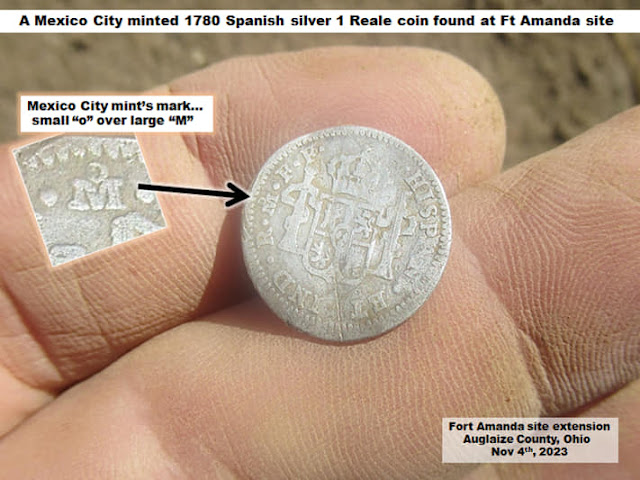

Coin Availability in 1794: At least 40 coins exactly like the one found at Fort Amanda have been found at the Loramies Store (Fort Loramie) site, the site that later became Wayne's Fort Loramie.

Horses : Internet searches and a discussion with veterenarian Gailbreath at OSU. It was agreed that while it was possible for a cavalry horse to travel up to 100 miles in a day in summer, winter weather posed several issues that could reduce that number to 25 miles.

Food for the horses:

A healthy military riding horse weighed between 800 and 1000 pounds.

The same horse needs 1.5% - 2 of its body weight a day in food. Being winter and using a mean weight of 900 pounds means each horse would need (.02 x 900) or 18 pounds of food. Multiply that by 17 horses (15 for the men and 2 oxen to pull a wagon. the total amount of food for the animals would have been over 300 pounds per day. Multiply that by 4 days and total weight of food for the animals would have been about 1200 pounds.

Food for the Soldiers

The men would have been issued a ration of at least 2 pounds per day. Multiply 15 soldiers by 2 pounds by 4 days and the weight of the food for the soldiers could have been as much 120 pounds.

Wagon: Wagons could carry up to 6 tons of supplies. Considering 120 pounds of food for the men, 1200 food for the animals and baggage, weapons and ammunition, tents, etc and one wagon would have been enough.

How far can a horse and rider normally travel in a day

In most cases, an average horse could travel about 10 to 20 miles when it snows and temperatures are low.

Winter conditions:

Traveling during the windy and freezing days without adequate protective gear will probably cause muscles to stiffen, while frozen ground causes pain in the animals hoofs.

Summer conditions:

Walk – 4 – 6 mph (Max travel distance = 40 miles)

Trot – 8 - 12 mph

Canter - 10 – 17 mph

Gallop - 25 - 30 mph

Military Rules for the Care of Calvary Horses

Efficiency of the horses:

Commanding officers must bear in mind that the efficiency of cavalry depends almost entirely upon the condition of the horses, which alone makes them able to get over long distances in short spaces of time. The horses must, therefore, be nursed with great care, in order that they may endure the utmost fatigue when emergencies demand it.

Gait of the horses:

The average march for cavalry is from fifteen to twenty miles per day. The walk is the habitual gait, but, when the ground is good, the trot may be used occasionally for short distances.

Length of march:

Long marches or expeditions should be begun moderately, particularly with horses new to the service. Ten or fifteen miles a day is enough for the first marches, which may be increased to twenty-five miles when necessary, after the horses are inured to their work.

Flankers:

In campaign, the usual precautions against surprise are taken, and an advanced guard and flankers are thrown out.

Halts and Rest

A halt of from five to ten minutes is made at the end of every hour, for the purpose of adjusting equipment, tightening girths, etc. . . . if there be grass, each captain first obliques his company a short distance from the road to let the horses feed, as horses must always be encouraged to graze as much as possible on the march. .

Rest Periods for Horses

On long marches, officers and men, except the sick, are required to dismount and lead from twenty to forty minutes every second or third hour; to save their backs, horses will be led over steep ground, and particularly down-hill.

Leaving ranks:

No enlisted man will be permitted to leave the ranks for any purpose, except on foot, leaving his horse.

Forming camp:

If the animals are to be subsisted by grazing, the camp should be formed early.

Watering the Horses:

It is sometimes necessary to encamp without water, to have grass for the horses; on such occasions, all animals must be watered within an hour of the last halt, and enough water carried forward to last the men for the night.”Summary

The key phrase in Wayne's Jan. 8 letter is

The remainder of this small party arrived in Camp in the

course of the next day.

If the route was Greenville directly to the Auglaize

While the normal walking speed of a horse in good conditions is 4 mph, because of the winter ice and snow and occasional rest periods I think it is safe to say they speed they traveled more like 3 mph. This would mean that to travel 44 miles in a day with 9 1/2 hours of daylight, even a non-stop trip would have taken 15 hours. If the soldiers left Greenville at 8 AM, and stopped just before sundown at 5:00 to set up camp they would have gone would have been approx. 27 and were still 17 miles from the Auglaize.

If the route was from Loramies Store to the Auglaize.

What if day 1, instead of going north to the Auglaize, they went northeast over to FT Loramie? Why would they do that? While most of the structures had been destroyed by George Rogers Clark in 1779, it is possible some shelters or parts of them were still standing. Another advantage is there was a well at the site and that would have provided the water supply for men and animals. From Loramie to the Auglaize is approx. 22 miles with the trip taking about 7 hours.

Conclusion

The keys to solving this mystery are mileage and daylight. If the soldiers left their their day 1 camp at 8 am, and traveled at 3 mph they would have gotten to the Auglaize around 2 PM. If the battle happened immediately and lasted just a few minutes, and they started back say around 2:30, they wouldn't have made it back to their day 1 camp until 8:30 that night, well after dark.

Based on the facts presented above, I think the battle Wayne referred in his Jan 8 letter did not take place near Ft. Amanda, but rather somewhere along the route, therefore negating the scenario of a soldier dropping the coin during a fight (Unless Greg Shipleys team discovers something in an upcoming dig that suggests otherwise)

The Answer to This Mystery?

OK, while I feel confident rulling out the possibilities that the coin was dropped by a Ft. Amanda soldier in 1812, a soldier passing by Amanda in 1812 and dropped by a soldier during a battle there, I do have one possibiliy in mind that may explain when, how and why the coin ended up at Amanda. I'll post that in my next blog.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Suggestions and comments welcomed