The Johnson Boys

1788

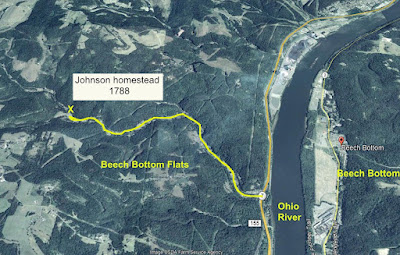

Henry Johnson was was born in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, on Feb. 4, 1773 and his brother John was born around 1775. The boys were sons of James and Catherine (Demoss) Johnson. The following is Henry's written account about how he and his brother escaped from the Indians.When I was about eight years old, my father having a large family to provide for, sold his farm with the expectation of acquiring larger possessions farther west. Thus he was stimulated to encounter the perils of pioneer life. He crossed the Ohio River and bought some improvements on what was called Beach Bottom Flats, two and a half miles from the river, and three or four miles above the mouth of Short Creek.

Captured

Soon after he came there, the Indians became troublesome. They stole horses and various other things and killed a number of persons in our neighborhood.When I was between eleven and twelve years old, I think it was in the fall of 1788, I was taken prisoner with my brother John, who was about eighteen months older than I. The circumstances are as follows: "One Saturday evening we were out with an older brother, and came home late in the evening; one of us had lost a hat and John and I went back the next day to look for it. We found the hat, and sat down on a log and were cracking nuts-after a short time we saw two men coming down from the direction of the house; from their dress we took them to be two of our neighbors, James Perdue and James Russell. We paid but little attention to them till they came quite near us. To escape by flight was now impossible and we had been disposed to try it. We sat still until they came up near us, one of them said, "How do, broder." My brother then asked them if they were Indians and they answered in the affirmative, and said we must go with them.

The Plan

"They conducted us over the Short Creek hills in search of horses, but found none; so we continued on foot. Night came on us and we halted in a low hollow, about three miles from Carpenter's Fort and about four miles from the place where they first took us. Our route being somewhat circuitous and full of zigzags we made headway but slowly. As night began to fall in around us I became fretful; my brother encouraged me by whispering to me that we would kill the Indians that night. After they had selected the place of encampment one of them scouted around the camp, while the other struck fire, which was done by stopping the touch holes of the gun and flashing powder in the pan.We took our suppers, and talked some time and went to bed on the naked ground to try to rest and study out the best mode of attack. They put us between them that they might be better able to guard us. After a while one of the Indians, supposing we were asleep, got up and stretched himself down on the other side of the fire and soon began to snore. John, who had been watching every motion, found they were sound asleep and whispered to me to get up. We got up as carefully as possible. John took the gun which the Indian struck fire with, cocked and placed it in the direction of the head of one of the Indians; he then took a tomahawk and drew it over the head of the other; I pulled the trigger and he struck at the same time; the blow falling too far back on the neck, only stunning the Indian; he attempted to spring to his feet, uttering most hideous yells. Although my brother repeated the blows with some effect the conflict became terrible and somewhat doubtful. The Indian, however, was forced to yield to the blows he received upon his head, and, in a short time, he lay quiet and still at our feet.

This remarkable act of heroism was recognized by the United States Government, for they granted these brothers a large tract of land that embraced the site of the killing of these two Indians. The boys later sold the land and moved into what is now Monroe County, where Henry told the above story

Now It's their Father's Turn

James Johnson, father of Henry and John Johnson was born in 1732 in Virginia. According to early writers, all his life James Johnson had been a frontiersman - first in Virginia, then in Maryland and later in Pennsylvania. His life had been full of stirring events and hardships. He had served in two wars, the French and Indian War and the War of Independence. He had undergone all the tests of skill and endurance of a Ranger on the frontier and had been in many encounters with hostile Indians. He is recorded as being "Strong, fearless and ambitious for his family." In 1785 he moved his young family through the wilderness from Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania into Jefferson County, Ohio where he built a small log cabin and cleared a few acres of land. The youngest of his large family was a daughter of five and the eldest a son of perhaps twenty-three. With two horses, a cow, and such farm implements and household articles as they could carry, they made their way to the banks of the Ohio, and then crossed it to their new home on Short Creek.

Carpenter's Fort had been built on Short Creek to protect the few families in the neighborhood from the troublesome Indians. Life was crude, simple and difficult.

Additional fields had to be cleared, fenced and planted before crops could be grown to carry them thru the coming winter. The log cabin had to be enlarged and log barns built for the live stock. Food and clothing had to be secured for the large family. There was plenty of hard work for James and his grown children. The Indians stole their horses and cattle, and killed a number of persons. It was quite as important to know how to use a rifle and to swing an ax. Within a few years with the help of the grown sons, productive fields were teeming with crops of corn, beans and buckwheat; a garden was providing vegetables; the buildings were made comfortable, and the spinning wheel and loom were humming.Carpenter's Fort had been built on Short Creek to protect the few families in the neighborhood from the troublesome Indians. Life was crude, simple and difficult.

The Johnson's Sure Had Bad Luck With Indians

In 1793, when he was passed sixty years of age, James Johnson was sent out from Fort Henry block house at Wheeling, Virginia, with Capt. William Boggs, Robert Maxwell, Joseph Daniels and a ___ Miller to explore the headwaters of Stillwater Creek, now in Harrison County. At night they were surprised by the Indians. Capt. Boggs was scalped after being shot. His companions fled, Johnson and two others succeeding in reaching the block house.Later that same year (1793) while in camp on McIntire Creek with ___ McIntire and John Layport, two neighbors, the Indians attacked them. James Johnson was captured after a hard struggle but his two companions were killed.

Likely route from capture to Sandusky

Approx. 140 miles

On one occasion British traders sought to obtain his liberty but without avail. He was released in 1795 as terms in Wayne's Greenville Treaty.

Even the Indians Thought The Boys Were Heros

Greenville, Ohio 1795

A group of Indians who were in Greenville at the time of the treaty signing asked one of Wayne's soldiers what had become of the two boys that killed the Indians 7 years earlier. When told that both of them were still at home with their parents, the leading Indian said, "You have not done right; you should have made them Kings."One More Thing. I forgot to mention James Johnson was my 5th Great Grandfather and his sons Henry and John were my 5th Great Uncles. And yes, I'm very very proud of them.