Before reading any further, click on the link below and turn up your sound

St. Clairs Defeat (Click on this link)

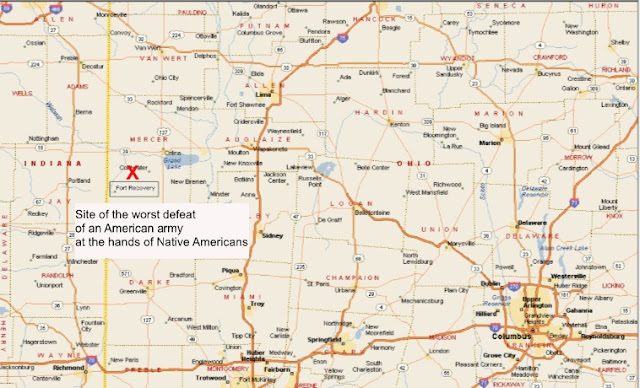

President Washington called on Arthur St. Clair, a 54- year-old Scottish-born Revolutionary War General, then serving as governor of the Northwest Territory to lead an army, return to Kekionga, destroy it and establish a permanent military post there. St. Clair was told he would be facing an enemy force of about 2,000 Indians led by Chief Blue Jacket of the Shawnee and Chief Little Turtle of the Miami along with a number of their British and Canadian allies. While he was told that he would be leading a 3,000 man army, he received only 2,000 and many of those individuals were either ill trained, poorly equipped or both. Also traveling with the army was a contingent of camp followers[1] and civilian contractors totaling another 200, half of whom were women and children. By late September, illness, deaths and desertions had reduced the size of his army from 2,200 to a total of 1,486.[2] St. Clair had no way of knowing it, but his army was already doomed.

In early October 1791, St. Clair’s army marched 30 miles northward and established Fort Hamilton on the east bank of the Great Miami River[3]. Once completed, they advanced another 45 miles where they halted and built Fort Jefferson. During construction, three men deserted. This had been an ongoing problem for St. Clair since leaving Fort Washington so when two of the three deserters were captured he had them hanged as a deterrent to others.

Meanwhile Little Turtle and Blue Jacket had been waiting patiently at Kekionga expecting an attack from St. Clair. Growing impatient, the two war chiefs decided to move their force of over 1,000 warriors southeast, hoping to intercept and engage the American force before they reached Kekionga. By the time the Indian forces reached the Wabash their number had grown to 1,400.

On November 3, 1791, St. Clair and his army arrived and set up camp on the banks of what he thought was the St. Marys River and within 20 miles striking distance of his objective. In reality, he was not camped on the St. Marys River; he was camped on the Wabash River and not within 20 miles of his objective, but rather 50 miles from his objective. The march had taken 47 days and during that time another 366 soldiers either died or deserted, an average of 8 per day. Apparently, hanging had not been a deterrent for desertion. The size of St. Clair’s force now stood at 1,120 (868 soldiers, 52 officers and 200 camp followers) nearly half its original size. Put into perspective, St. Clairs 920 soldiers were about to come face to face with 1,400 Indian warriors.

The weather was colder than normal for that time of year in Ohio and the ground was covered with a light blanket of snow. As St. Clair’s men slept, the enemy quietly encircled their camp and went into cold camp - meaning no fires were to be built. Each warrior covered himself in blankets and furs and lay on the cold ground in absolute silence waiting for the word to attack the following morning. Scattered gunshots were heard throughout the night but were dismissed as overreaction by nervous sentries.

The Hounds of Hell Are Released[4]

At 7:15 am, Friday, November 4, 1791, blood-curdling screams rang out from the surrounding woods as more than 1,400 warriors poured into the encampment from every direction, killing everyone and everything in sight including horses, cattle, men, women and children. The Indians quickly identified and killed the officers first in order to create confusion among the soldiers. So effective was this tactic that within the first few minutes, over half of the forty-three officers either were killed outright or lay dying on the ground. Survivors later described men standing around dazed, wandering around and confused as to what to do. Some threw their muskets down hoping to surrender only to be tomahawked and murdered where they stood. Survivors told stories of seeing younger soldiers, their first time in combat, standing motionless and confused, and some crying for their mothers. It was total pandemonium.

In just a matter of a few minutes, the cold air mixed with the acrid smoke from the muskets and cannon made seeing objects a few feet away virtually impossible. St. Clair, who suffered with severe gout was in constant pain at the time and had to be lifted onto his horse. Almost immediately, the horse was shot through the head, killing it instantly throwing St. Clair to the ground. The General shouted for another horse and as the soldier was rushing toward him with the second horse; both the man and animal were shot down. Screaming frantically for a third horse, St. Clair was hoisted into the saddle where he began yelling orders. At one point, a bullet passed so close to his head that it cut off a lock of his hair. A later examination found that eight bullets had passed through his clothing during the battle. Those individuals too injured to move or frozen by fear were murdered on the spot. Others huddled together in small groups and were shot down like animals herded into a slaughtering pen.

An artillery crew tried to turn its guns in the direction of the main body of Indians but snipers killed most of the gun crew forcing the others to spike[5] the cannon and abandon it. One survivor recalled years later that one of the scenes he remembered most vividly was seeing what he thought were pumpkins with steam rising from them. When the smoke cleared, he realized what he was actually seeing was the scalped heads of the gun crew and the steam was the heat vapor rising from the top of the scalped heads. The attack had been fast and complete, killing everyone assigned to the gun. The battle raged on for two and one-half hours with an American killed an average of every 10 seconds. Around 9:45 am, sensing imminent annihilation, St. Clair screamed orders to what was left of his army to retreat to Fort Jefferson, 30 miles to the south.

To help open a path for the retreating amy, Colonel William Darke ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge the main Indian position. The Indians retreated to the woods but as Darke’s men continued after them, the Indians fell in behind and killed many of them. Warriors ran after the retreating soldiers for two miles killing those too slow or too wounded to keep up with the others. Some soldiers removed their bayonets and stuck them in the ground pointing backwards toward the enemy, hoping it would slow them down.[6]

By 10 o’clock that morning, most of the smoke from the muskets and cannons had cleared. Survivors described the battlefield as absolute carnage. Dead and mutilated bodies of hundreds of soldiers, women, children, horses and pack animals littered the ground. Many of the women’s bodies had been mutilated in the most heinous ways and young children were swung by the legs bashing their heads against trees, literally knocking their brains out. The warriors continued their gruesome work of stripping the dead and dying of valuables such as warm winter clothing, muskets, pistols, swords, knives, powder horns, tents, pots, pans, utensils and other camp materials.

On November 8, St. Clair’s army, or what was left of it, staggered back into Fort Washington[7]. For the next several days, the General worked on his report to the Secretary of War outlining details of the battle. He finished it on November 18 and the following morning dispatched a courier with instructions to carry it to Secretary of War Knox in Philadelphia. The courier arrived in Philadelphia a month later on December 19 and delivered the report to Knox. The following day, Knox met with President Washington who was having dinner with friends at the time. The two men adjourned to a separate room where Knox informed Washington of the disaster. Knox later wrote that Washington returned to his dinner guests where he retained his composure throughout the rest of the evening but when the guests left, he “unleashed his rage.”[8] He purportedly shouted to his secretary “St. Clair allowed that army to be cut to pieces, butchered, tomahawked by surprise. How can he answer to his country? The curse of widows and children is upon him.” [9] The following month, St. Clair traveled to Philadelphia to give his account of what had happened. Blaming the quartermaster as well as the War Department, St. Clair asked for a court-martial hoping he would be exonerated, after which he would resign his commission. Washington not only denied St. Clair’s request for a court-marshal, he demanded his resignation effective immediately.[10]

The Aftermath

The battle, known as St. Clair’s defeat, has gone down in history as the worst defeat of a United States Army at the hands of Native Americans. Nearly one-quarter of the entire United States Army had been slaughtered in a single three-hour battle. While the exact number of killed will never be known, the best estimates are that 632 officers and soldiers were killed outright or died on the battlefield and another 264 were wounded. Of the nearly 200 women, children and contractors, at least 50 of the women weer killed and the number of children killed is unknown. Three spots were identified where prisoners were tortured and burned at the stake. Indian losses that day were estimated at only twenty-one killed and forty wounded. Of St. Clair’s 920-man force, only 24 men returned to Fort Washington unharmed. The Army’s casualty rate (killed and wounded) was a staggering 97% while the casualty rate of the Indians was less than 5 percent.

In February 1792, nearly 3 months after the battle, General Wilkinson, ordered Captain Robert Buntin to assemble a detachment of men and return to St. Clair’s battlefield to look for salvageable materials and to bury the dead, or at least what remained of them. In his report to Wilkinson, Buntin wrote:

In my opinion, those innocent men who fell into the enemy’s hands with life were used with the greatest torture, having their limbs torn off; and the women have been treated with the most indecent cruelty having stakes as thick as a person’s arm driven through their bodies. The first I observed when burying the dead and the latter was discovered by Col Sergeant and Dr Brown. We found three whole carriages (cannon); the other five were so much damaged that they were rendered useless. By the general’s orders, pits were dug in different places and all the dead bodies that were exposed to view or could be conveniently found (the snow being very deep) were buried. Six hundred skulls were found and the flesh was entirely off the bones and in many cases the sinews yet held them together.

Accompanying Buntin was a man named Sergeant who wrote in his report:

“I was astonished to see the amazing effect of the enemy’s fire. Every twig and bush seems to be cut down, and the saplings and trees marked with the utmost profusion of shot.”

By 1792, the stakes had been raised considerably in terms of national security. Not only was there a major concern with the continuing Indian hostilities in the northwest, there was an equally growing concern that the disastrous campaigns of Harmar and St. Clair could create the impression that the United States was weak and incapable of dealing not only with her internal problems with the Indians, but equally incapable of defending herself against foreign powers as well. What the country needed was a victory and it was and it was about to get one a major one. Leading it was General Anthony Wayne and he successfully defeated the Indians in 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near Maumee, Ohio.

Put into a Gruesome Perspective

For my neighbors, laid end to end, the bodies of the fallen would have measured 4,784 feet (3/4 of the distance around the loop) . Custers would have measured 1541 feet

[1] Camp followers were civilians who traveled with the army and provided services to soldiers, the army did not, including such things as laundresses, cooks, prostitutes, liquor, writing paper, ink, etc.

[2] http://military.wikia.com/wiki/St._Clair%27s_Defeat

[3] Hamilton, Ohio. The fort was located on the south bank of the Great Miami River where High St. crosses.

[4] The artwork of the battle was created by Peter Dennis and is found in the book, “Wabash 1791 St. Clair’s defeat” by John F. Winkler (Osprey Publishing).

[5] Spiking involved shoving a metal rod or bayonet tips down into the primer hole of the cannon and breaking it off in the hole thus making it impossible to fire the piece.

[6] John Winkler’s Book, “Wabash 1791 – St. Clair’s Defeat,” is a must reading for those interested in the events leading up to the battle and in a minute by minute account of the battle itself.

[7] Cincinnati, Ohio.

[8] http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Clair%27s_Defeat

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Arthur_St._Clair

[10] Artwork created by Peter Dennis and published by Osprey Publishing.